The first month of 2017 has seen a lot.

But we will limit ourselves here to the new research that has been published on voice-hearing, which this month includes aspects such as trauma, neurology, psychics, and suicide.

Trauma and voice-hearing

Mette Nygaard and colleagues examined voice-hearing in 181 refugees with PTSD.

Mette Nygaard and colleagues examined voice-hearing in 181 refugees with PTSD.

The majority came from Western Asia (Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, Turkey). Most had experienced torture and imprisonment. Most had lived in a war zone.

74 of the 181 refugees with PTSD (i.e., 41%) had ‘psychotic experiences’.

The first question this paper allows us to answer is what the rates of hallucinations were in the overall sample of refugees with PTSD. This was a question which the authors didn’t focus on, but which I’m interested in as Eleanor Longden and I have argued that hearing voices should be a named symptom of PTSD.

Below are the rates in the overall sample (based on a review of medical records)

| Rates of hallucinations in all refugees with PTSD (N=181) |

| Auditory hallucinations (any auditory experience) |

27% |

| Auditory hallucinations (specifically voices) |

17% |

| Visual hallucinations |

12% |

| Olfactory hallucinations |

3% |

| Tactile hallucinations |

3% |

Elsewhere I’ve estimated rates of voice-hearing in PTSD to be about 25%, so this in the ballpark we would expect.

The next question the paper answers is what these hallucinations were like.

Voices could be of known people (e.g., family members, perpetrators of abuse) or unknown people (“hearing people talking together”, “hearing voices from angry men”,“hearing children calling”). They could be commanding (“voice telling him he should shave his hair off”) and abusive (“hearing voices saying she is not worth anything”, “hearing reproachful voices from lost friends”).

Visual hallucinations included formed figures of family members (“see father, know it’s not real”, “get visits from brother, mother and neighbour’s dog”), people who had abused them (“see men responsible for torture approximately every second day”) or other things (“see dangerous animals showing their teeth”). Others saw unformed hallucinations such as shadows and ghosts.

Now, you may be wondering how many of these hallucinations could be said to be flashbacks (which are already named as a characteristic symptom of PTSD). The authors note that only five refugees had hallucinations described as being directly connected to flashbacks (e.g.; “angry voices in connection with flashbacks”, “flashbacks with airplane noise”.)

The paper then reports data on the rates of different modalities of hallucinations in the subset of refugees with PTSD who had ‘psychotic experiences’

| Rates of hallucinations in refugees with PTSD with psychotic features (n=74) |

| Auditory hallucinations (any auditory experience) |

66% |

| Auditory hallucinations (specifically voices) |

41% |

| Visual hallucinations |

30% |

| Olfactory hallucinations |

7% |

| Tactile hallucinations |

8% |

Incidentally, this distribution of hallucinations is uncannily similar to that found in people diagnosed with schizophrenia. For example, in a paper which will be shortly be published by myself, Rob Dudley, and colleagues [McCarthy-Jones, S. et al. (accepted). Occurrence and co-occurrence of hallucinations by modality in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Research] we found the following lifetime rates of hallucination by modality:

| Modality |

Ireland |

Australia |

| (n=205) |

(n=218) |

| Auditory |

64% |

80% |

| Visual |

23% |

31% |

| Olfactory |

6% |

10% |

| Tactile |

9% |

19% |

The incidence of hallucinations by modality in schizophrenia and PTSD with psychotic features hence seem highly similar. Why are we set up to hallucinate in this way?

Anyway, it is clear from this paper that traumatised refugees who develop PTSD may well come to experience hallucinations. This needs to inform the services we provide for people and the form those services take.

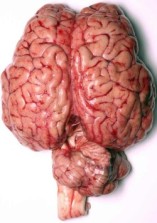

Neurology

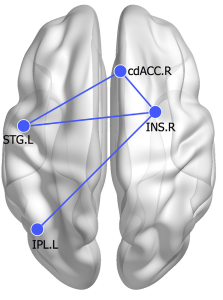

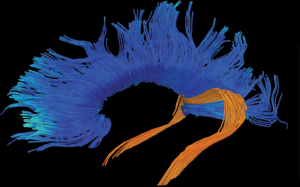

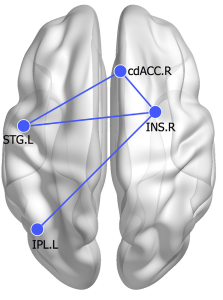

Two neuroimaging studies this month both pointed at a role for a part of the brain called the insula in voice-hearing. First, Alonso-Solís and colleagues reported altered neural activity in the insula in people diagnosed with schizophrenia who heard voices (when compared to people diagnosed with schizophrenia who did not hear voices). Second, Chang and colleagues reported altered connectivity between the insula (in the right hemisphere) and a range of other neural regions in medication-naive people diagnosed with first episode schizophrenia who heard voices (compared to equivalent patients who did not hear voices).

The theory behind an involvement of the insula in voice-hearing is that this region of the brain plays a key role in the brain’s salience network. When something is made salient to you, you attend to it; it ‘pops out’ at you.

The Chang et al. study was particularly interesting as it found evidence of altered neural connectivity in the specific regions shown on the right to be associated with voice-hearing.

The Chang et al. study was particularly interesting as it found evidence of altered neural connectivity in the specific regions shown on the right to be associated with voice-hearing.

These included altered connectivity between the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and the superior temporal gyrus (STG). The ACC is thought to help monitor whether experiences are internally or externally generated. The auditory cortex lives in the STG. Altered connectivity between these two regions is hence thought to reflect the ACC failing to regulate the STG as it normally would, leading to internally generated thoughts being mislabelled as other people’s voices. Chang and colleagues also found altered connectivity between the insula and the STG, which could be interpreted as leading to an alteration to the salience of thoughts. Connectivity was also altered between the insula and ACC. As Chang and colleagues note, the co-activation of these regions is associated with the detection and response to salient stimuli in the environment. Thus their findings are consistent with voices having origins in self-generated thoughts that the brain makes more salient and fails to correctly monitor.

A final study to mention on the neuroimaging front was one which looked at resting cerebral blood flow in people diagnosed with schizophrenia who heard voices. This also found voice-hearing to be associated with changes in a part of the brain associated with signalling salience; the striatum. It also pointed to auditory cortex changes associated with voice-hearing, but in the right, not left hemisphere.

The meanings of voice-hearing

This section starts with a great study from Powers, Kelley, and Corlett. This interviewed clairaudient psychics who received daily messages from voices. It then compared their voices to those heard by help seeking voice-hearers (people diagnosed with a psychotic disorder who heard voices).

First, have a look at the huge difference in ages between when the psychics, on average, first heard a voice, and when the people with a diagnosed psychiatric disorder first heard a voice (see right).

First, have a look at the huge difference in ages between when the psychics, on average, first heard a voice, and when the people with a diagnosed psychiatric disorder first heard a voice (see right).

One has to suspect from this that two very different processes are going on here.

In terms of how the voices of the two groups compared, they were mostly similar in terms of their auditory characteristics, content, structure, syntax, and frequency.

However, the psychics were more able to control their voices (i.e., to be able to start and stop them), although this control was not always total. For example:

Researcher: When do the voices happen?

Psychic: If I allow it, it can happen all the time. Sometimes I can put a wall up, but if its meant to be heard or seen, it will be.

Another psychic stated: “when you’re open it will come. But it takes work.”

Another explained they could shut the voices off simply by telling them to shut up; “I tell them to shut up… I say it out loud…”I’m off duty now. Go away.”

Consider also how the psychics wanted to hear their voices. One said:

“I’ve done a lot of meditation techniques to just make sure that the voices are clear so that

I can understand the message.”

This is very different to a process of trying to block out or dampen down the voices with antipsychotics. Indeed, it reminds me of reports of some patients smoking pot in order to make their voices louder and clearer, so that they could be better understood and coped with.

Other differences were that the psychics were less likely to find their voices bothersome, more likely to think they helped their personal safety, and more likely to think the source of the voices was God or another spiritual being.

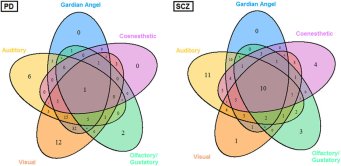

Other potential differences hinted at in the paper were that the voices heard by the patients were more likely to be replays of things previously thought or spoken, and that the psychics’ voices were more likely to co-occur with other forms of hallucinations.

In term of other papers on the meanings of voice-hearing, a paper entitled “Hopeful conversations about voice hearing” explored one person’s experiences of voice-hearing in depth. Once I can get hold of a copy of this paper, I will add more on this.

Cognition

A study by Sara Siddi and colleagues found that set-shifting skills were worse in people diagnosed with a psychotic disorder who heard voices than in those who did not. Set shifting is the ability to move your attention from one task to another. The authors suggest this may be a mechanism underlying voice-hearing, although are not entirely how.

Clinical

Slotema and colleagues found that, in people diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, the experience of hearing voices was associated with more suicide planning and attempts.

An article, written in Dutch, whose title in English is “A personal diagnosis for patients who hear voices: symptoms can improve in a meaningful context” was published this month. In this, Corstens and Romme argue that making a ‘personal diagnosis’ for someone who hears voices can allow one to establish a relationship between the voices and events in a patient’s life, empower the patient, and, through revealing possible ways of solving the patient’s personal problems, lead to further treatment and recovery. If anyone has a copy of this in English, please let me know. Dank je!

Finally this month, a literature review from the University of Malta tried to assess the effectiveness of antipsychotic medication relative to the Hearing Voices Approach. It concludes that “it was not possible to conclude which one has the most beneficial outcomes”. I’m yet to get a copy of this to read myself, but will update this in due course. If you’re interested in issues in researching the Hearing Voices Approach, a paper led by Dirk Corstens, published in 2014, may be of interest.

Other things of interest

A podcast from Prof Pat Waugh on Virginia Woolf, including her voice-hearing experiences.

A powerpoint presentation on psychosocial interventions for distressing voice-hearing.

Wrap-up

That’s all for this month. For those of you within striking distance of Durham, it would be well worth a trip to hear these talks later this month:

And to see the art installation ‘Tuning into the Light: Experiencing Celestial Voices’ (11-25 Feb)

You can find out more about the fabulous voice-hearing related events taking place in Durham, organised by Charles, Angela, and the rest of the Hearing the Voice team at http://hearingvoicesdu.org/

As next month sees Valentine’s Day upon us, I thought I’d leave you with a paper on love and voice-hearing that myself and Larry Davidson penned a number of years ago.

Hope to see you again next month (hang on in there my American friends).

SMJ

It’s been a while. Not only a great song by Staind, but also an accurate observation on when I last gave you an up-to-date blog.

It’s been a while. Not only a great song by Staind, but also an accurate observation on when I last gave you an up-to-date blog. Two simple questions that have changed the way people hear inner voices.

Two simple questions that have changed the way people hear inner voices. It’s nearly World Hearing Voices Congress time again. It’s Boston this year, from Aug 16th-18th. Here’s a nice pre-conference blog by Sera Davidow.

It’s nearly World Hearing Voices Congress time again. It’s Boston this year, from Aug 16th-18th. Here’s a nice pre-conference blog by Sera Davidow.

An establishment of what the key elements of

An establishment of what the key elements of